How did photography evolve from the early days of daguerreotype to today’s digital cameras? What was the impact of the invention of the camera on society?

Photography has always played a major role in our lives. From capturing memories at weddings and birthdays to documenting historical events, it has become an integral part of everyday life.

From the earliest photographic processes to modern day digital cameras, the history of photography has evolved over time. The invention of the camera changed the way we view the world around us. In this article, we take a look back at some of the key moments in the evolution of photography.

Before Photography

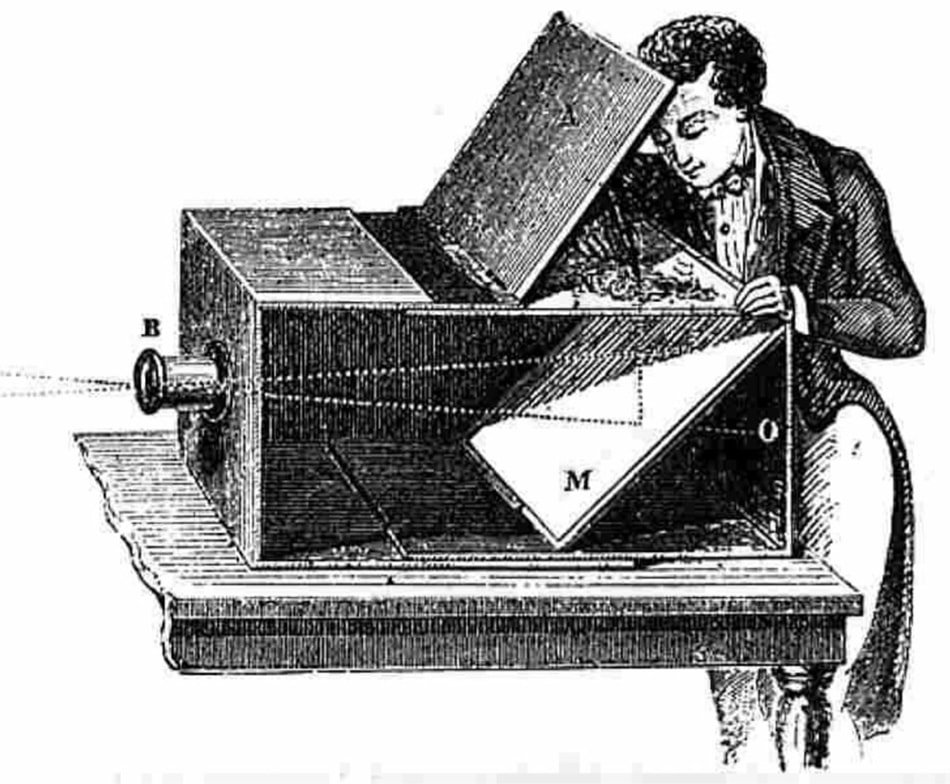

The antecedent of the camera was the Camera Obscura, which consisted of a dark room with a hole in one wall, through which images of objects outside the room were projected onto a second wall. The Chinese and ancient Greeks such as Aristotle were likely aware of the principle more than 2,000 years ago.

Giambattista della Porta, an Italian scientist and writer, demonstrated and detailed the use of a camera obscura with a lens late in the 16th century. While artists used variations on the camera obscura to create images they could trace in subsequent centuries, the results were dependent on the artist’s drawing skills, so scientists continued to search for a method to reproduce images completely mechanically. They could project the image on the wall or piece of paper, however no printing was possible at the time: recording light turned out to be a lot harder than projecting it. The instrument that people used for processing pictures was called the Camera Obscura (which is Latin for the dark room) and it was around for a few centuries before photography came along.

The Birth of Camera

Several centuries earlier, during the Renaissance, painters began to utilise a primitive “camera” known as a camera obscura. (a Latin phrase literally meaning “darkroom” from which our present word “camera” is derived) to more faithfully replicate nature through art. It is believed that the camera obscura was invented between the 13th and 14th centuries; nevertheless, a 10th-century document by the Arabian scholar Hassan ibn Hassan describes the concepts upon which the camera obscura and modern analogue photography are based.

The Camera Obscura is essentially a dark, closed space shaped like a box with a hole on one side. The hole must be small enough in proportion to the box for the camera obscura to function properly. Light entering through a tiny hole transforms and creates an image on the surface it meets, such as the box’s wall. However, the image is flipped and upside down, which is why modern analogue cameras use mirrors.

Giovanni Battista della Porta, an Italian scholar, wrote an essay in the mid-16th century on how to use camera obscura to make drawing easier. He projected images of people outside the camera obscura onto the canvas inside (the camera obscura was a rather large room in this case) and then drew over or attempted to copy the image.

Joseph Nicephore Niepce created the first photographic image using a camera obscura on a summer day in 1827. Niepce engraved an image onto a bitumen-coated metal plate and then exposed it to light. The dark sections of the engraving prevented light from reacting with the chemicals on the plate, while the lighter areas allowed light to do so.

When Niepce immersed the metal plate in a solvent, a picture gradually emerged. These heliographs, also known as sun prints, are considered the earliest photographic images. Nonetheless, Niepce’s technique took eight hours of light exposure to produce a picture that would quickly fade. Later came the capacity to “fix” or permanently alter an image.

View from the Window. Image: public domain via Wikipedia

The Birth of Photography – World’s First Photograph.

In 1826, the French scientiest Joseph Nicéphore Niépce captured the the world’s first photograph entitled View from the Window at Le Gras at his family’s rural home.

Daguerreotype Process

Frenchman Louis Daguerre also experimented with ways to capture an image, but it took him a further decade before he was able to cut exposure time to less than 30 minutes and prevent the image from afterwards vanishing. According to historians, this was the first practical method of photography. In 1829, he partnered with Niepce to enhance the process Niepce had created. After several years of experimentation and Niepce’s death in 1839, Daguerre created a more practical and effective method of photography, which he named after himself.

The first step in Daguerre’s daguerreotype method was to fix the images onto a sheet of silvered copper. He then polished the silver and covered it with iodine to create a light-sensitive surface. The plate was then exposed for a few minutes in a camera. After the picture had been painted by light, Daguerre immersed the plate in a silver chloride solution. This procedure produced an image that will not fade when exposed to light.

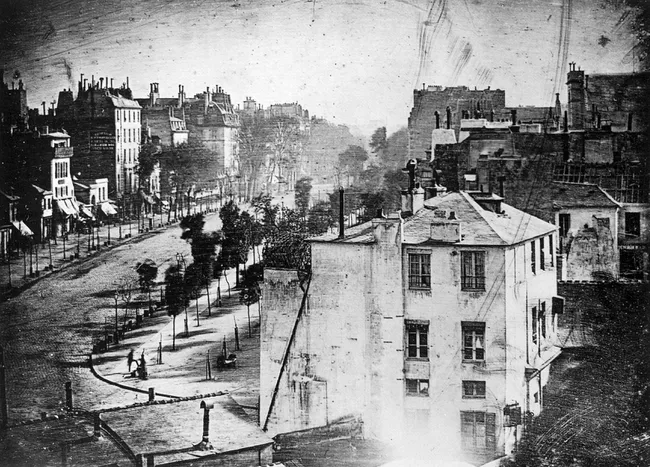

First humans to be photographed in history. Image: public domain via Wikipedia

First ever Photograph of a Human – The World’s First Photograph With a Human

A photograph of a street in Paris taken in 1838 may have been the first-ever photograph of a human being. Photographs taken by Louis Daguerre, the creator of the Daguerreotype process.

In 1839, Daguerre and Niepce’s son sold the daguerreotype patent to the French government and issued a pamphlet detailing the technique. The daguerreotype achieved rapid popularity in Europe and the United States. In New York City alone, there were approximately 70 daguerreotype studios by 1850.

August 19, The day the daguerreotype went public is considered as the World Photography Day.

On August 19 of the same year that is 1839, when permanent photograph and the Daguerreotype process came into existence, French Government made the process as public domain or say “Free to the World.”

Talbot’s Process

Fox Talbot introduced the Calotype method a few weeks after announcing the daguerreotype to the public. He photographed with his own camera. This is the first time we encounter the concepts of a positive and negative image. Both the stabilisation of the negative and the subsequent positive print were referred to as photogenic drawing. By 1839, Talbot’s positive photogenic drawings were vibrant, blurry, and somewhat sensitive.

Talbot made paper light-sensitive with a silver-salt solution. The paper was then exposed to light. The background turned dark, while the subject was shown in grayscale. This was a negative image. Talbot generated contact prints from the paper negative, inverting the light and shadows to create a detailed image. In 1841, he refined this paper-negative process and named it calotype, which derives from the Greek for “beautiful picture.”

English sculptor Frederick Scoff Archer devised the wet-plate negative in 1851. He coated glass with light-sensitive silver salts using a viscous solution of collodion (a volatile chemical based on alcohol). This wet plate produced a more solid and detailed negative since it was made of glass instead of paper.

Alexander Wolcott founded the first known photographic studio in New York City in March 1840

Alexander Wolcott founded the first known photographic studio in New York City in March 1840, when he launched a “Daguerrean Parlor” for tiny portraits, using a camera with a mirror replaced for the lens. Richard Beard opened the first studio in Europe on March 23, 1841, in a glasshouse on the roof of the Royal Polytechnic Institution in London.

The Cyanotype Processes

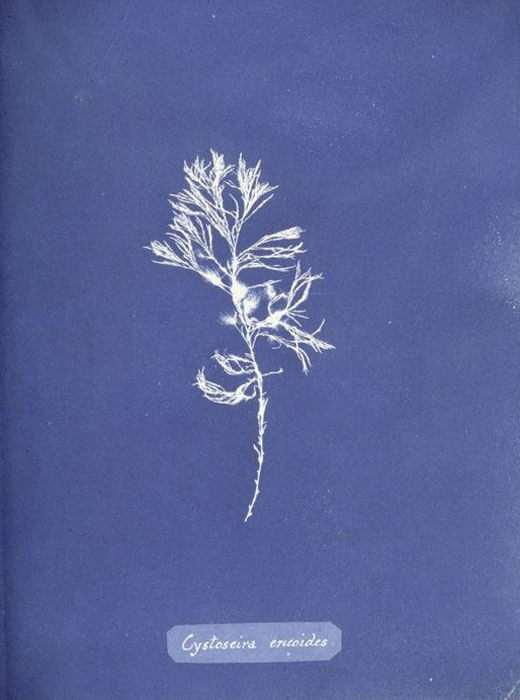

Photochemical blueprinting (also known as the cyanotype process, derived from the Ancient Greek kyanos-blue) is one of the earliest photography processes that produce intensely blue images. Sir John Frederick Herschel, an English natural scientist and astronomer, devised this method in 1842. (1792-1871). Cyanotype was thus the third photographic technique after daguerreotype and talbotype (calotype) that allowed for the production of stable photographic images.

World’s First Photo Book

Anna Atkins, an English botanist, published Photographs of British Algae in 1843, which is possibly the first book to be illustrated with photographs. She had mastered cyanotype, a new photographic technique developed by Sir John Herschel the year prior.

The Cyanotype pictures can be created in one of two ways: by utilising a photo negative or by placing an object directly on sun-exposed paper. Everywhere the object blocks the light, the paper will remain white, and wherever the light hits surrounding the object, the paper will react by turning blue. Until the advent of modern photocopiers, the method was ideally suited to its original function of duplicating technical drawings, which was its most prevalent application in engineering and architecture.

The Collodion Processes

The invention of the wet collodion method for producing glass negatives in 1851 changed photography. This new process, developed by English sculptor Frederick Scott Archer, was 20 times faster than all prior procedures and was also patent-free. The collodion technique, sometimes known as the “collodion wet plate process,” needs the photographic material to be coated, sensitised, exposed, and developed in roughly fifteen minutes, necessitating the use of a portable darkroom in the field.

The Albumen Print

Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard published the albumen print, also known as the albumen silver print, in January 1847. It used albumen contained in egg whites to bind the chemicals to the surface of the paper. The albumen printing method provided photographers with higher detail reproduction, a larger tonal range, and more print durability than the salted paper procedure that came before it.

The Platinum Print

From the late 1880s through the early 1920s, Alfred Stieglitz’s preferred procedure was the platinum print, or “platinotype.” The platinum printing technique is based on the properties of light-sensitive iron salts that react with platinum salts to produce platinum metal. To make paper light sensitive, a solution of these salts is applied to a sheet of paper.

The Pigment Processes

Heliography Process

The Woodbury type

The Woodbury type was invented by Walter B. A Woodbury Type is a photo-mechanical process where a layer of colored gelatin is placed on top of a piece of paper and then pressed into a mold. The mold is made by photographing a negative and varying its thickness depending on the light and dark areas on the negative. When the colored gelatine is pressed against the paper it takes the shape of the variations and makes the tonal gradation.

The Glatin Silver Process

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, the gelatin silver method dominated black-and-white photography. A negative or positive print’s paper or film is covered with an emulsification including gelatin and silver salts. Because gelatin silver prints and negatives are developed rather than printed, exposure to light registers a latent image that becomes apparent only when developed in a chemical bath. Printing periods for this method are quicker than for previous printed-out procedures such as salted paper prints and albumen prints.

Color Photography Process

On the basis of the theory demonstrated by James Clerk Maxwell in the 1860s, they reproduced colour by combining red, green, and blue light. These colour processes are known as “additive” processes. First introduced in France in 1907 by Louis and Auguste Lumière, Autchrome was the first generally useful color photographic process. One year later, in 1937, the Agfa Company introduced the Agfacolor negative–positive process.

First Colour Image

The first colour image was taken in 1861 by Thomas Sutton using the three-color system proposed by James Clerk Maxwell in 1855. The topic is a colourful ribbon, which is sometimes referred to as a tartan ribbon.